With the UK’s ban on fracking for shale gas in England – that has been in place since 2019 – now formally lifted, we look at the technology involved and how fracking fits in with the idea of sustainability.

What Is Fracking?

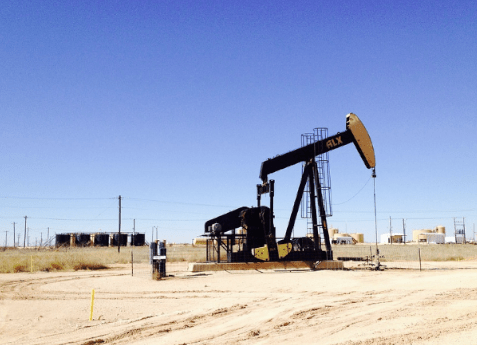

Fracking is the term for drilling into geologically complex layers of rock and pumping a mixture of pressurised water, sand and chemicals at a shale rock layer to release the oil and gas inside.

What Was It Banned?

Fracking in the UK was banned after the industry regulator, the Oil and Gas Authority (OGA), said it was not possible to predict the magnitude of the earthquakes it might trigger. For example, back in 2018, the British Geological Survey reported that 120 seismic events (earth tremors) were detected during the drilling for fracking at Cuadrilla’s site at New Preston Road in Blackpool.

There were also concerns that the chemicals used in fracking could find their way into (and contaminate) the water supply.

Why Is It Back On?

After New Prime Minister Liz Truss said earlier this month that fracking would be allowed, plus Business and Energy Secretary Jacob Rees-Mogg having said that in the light of the oil and gas problems resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, all domestic sources of energy needed to be explored, the ban on Fracking in Britain has been lifted.

What Technology Does Fracking Use?

Although early experiments took place in the 1940s, the modern method for fracking is reported to have been developed by an oil company worker who was trying to turn around the failing fortunes of an area with natural gas wells called Barnett Shale in Texas back in 1995. There are many different types of possible fracturing technologies that could be used but hydraulic fracturing technology is the main one.

Since fracking involves drilling a long way down into the earth to somewhere that is not visible, geological knowledge and computer models are used in fracking. Back in 2019, for example, the UK government conducted a review of software used by the oil and gas industry to model hydraulic fracturing, to help the Environment Agency to understand what the computer models did, how they operated, and what information they could give to help assess environmental risk at individual sites.

At the time, seven modelling packages were identified as the most common, each with different levels of sophistication, and each providing different results. It was concluded that the capacity to simulate any effects of induced fractures on existing fracture networks was important, and that a reliance on hydraulic fracturing simulators alone as proof of compliance was not feasible, especially in new areas of exploration. The review suggested that techniques such like geophysical monitoring would help to confirm simulations.

How Sustainable Is Fracking?

Back in 2018, research from The University of Manchester looked at the environmental, economic, and social sustainability of shale gas in the UK and compared it to other electricity generating options such as coal, nuclear, natural gas, liquefied natural gas (LNG), solar photovoltaics (PV), wind, hydro and biomass. The study concluded that fracking is one of least sustainable options for producing electricity, any future electricity mix would be more sustainable if it had a lower rather than a higher share of shale gas, and that huge improvements would be needed for shale gas to be considered as sustainable options like wind and solar PV.

Also, campaigners opposing fracking say that, given that shale gas is a fossil fuel, and that global warming is a major issue, energy firms and governments may be better investing renewable and green sources of energy.

What Does This Mean For Your Organisation?

There are differing theories and opinions about how much gas could actually be obtained from fracking. Even the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, Kwasi Kwarteng, was recently reminded of something he was quoted as saying back in March 2022 (when he was business secretary): “No amount of shale gas from wells across rural England would be enough to lower European price any time soon.” Prime Minister Liz Truss has said recently that developers will be only given permission “where there is local support”, but there is likely to be considerable opposition from campaigners and protesters wherever fracking resumes.

Organisations of all kinds now face the challenge of higher energy bills, plus the country also faces supply challenges caused by Russia’s war against Ukraine. Some commentators don’t believe that fracking in the UK will be enough to bring down energy bills significantly unless the government can agree a price with the fracking companies.

It remains to be seen how fracking in Britain proceeds from here, but with much opposition, it is likely to be a bumpy ride.

By Mike Knight